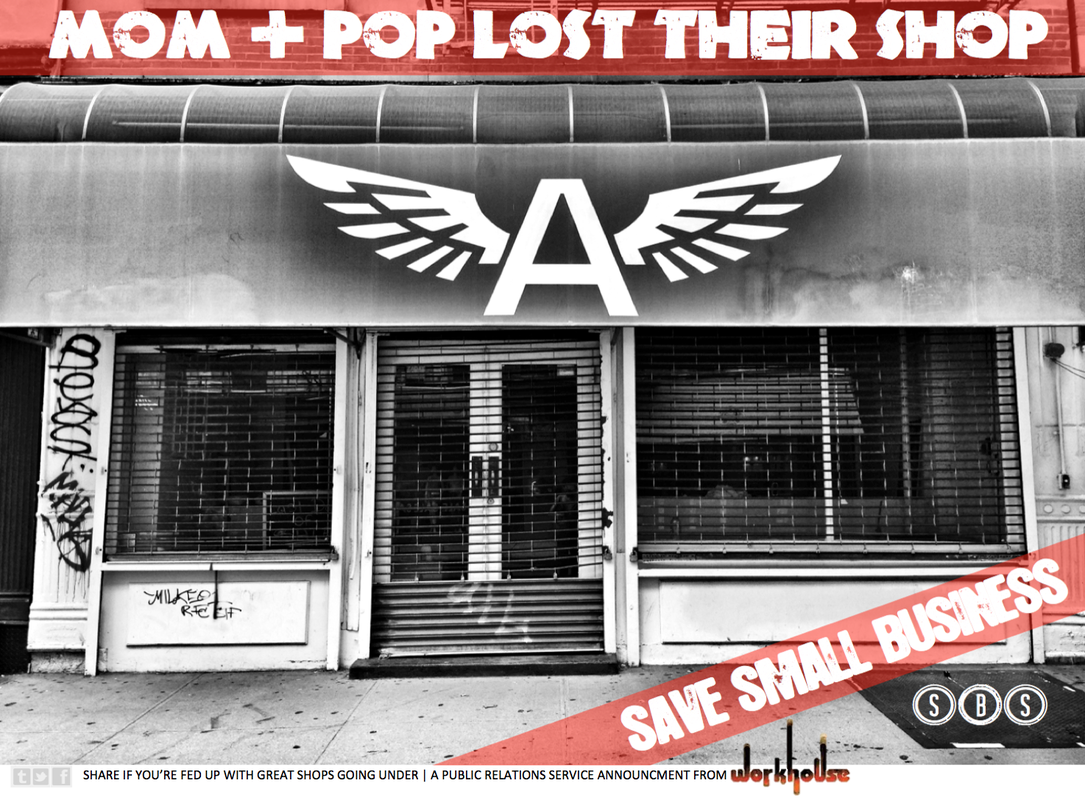

UNIQUE & ORIGINAL BUSINESSES ARE CLOSING IN NEW YORK

HERE'S A LOOK AT THE STORIES & REASONS WHY A LAND-STARVED CITY IS

CLOSING MOM & POP DOWN

#SAVENYC

IMAGES COURTESY OF ADAM NELSON | WORKHOUSE | WWW.WORKHOUSEPR.NET

NEW YORK CITY: Today, more than ever, the soul of New York is getting mugged by rising rents, suburbanization, rampant development, and a flood of chain businesses. Hyper-gentrification is destroying the cultural fabric of New York and City Hall is doing nothing to stop it. #SAVENYC (SaveNYC.Nyc) is a call to action that gathers the voices of everyday New Yorkers, celebrities, small businesspeople, tourists —all who care about protecting the cultural fabric of the city — to send a strong message to City Hall: Save New York! Cultivated by former mayor Bloomberg, hyper-gentrification in New York was implemented via strategically planned mass rezonings, eminent domain, and billions in tax breaks to large corporations. This has led to the ongoing eviction of countless small businesses, destroying the fabric of our streets and putting the city’s soul on life support. To save it, we need politicians, activists, and citizens to get tough and protect the city’s cultural heritage so we don’t lose anymore like CBGB’s, Cafe Edison, Colony Records, Florent, Lenox Lounge, 5Pointz, and many, many others. With the #SaveNYC campaign asks readers to submit first-person video testimonials and stories to tell New York and its leaders why the cultural heritage of the city matters, and why it needs protecting–before it’s too late. Interested media who would like to learn more about #SaveNYC please contact WORKHOUSE, CEO Adam Nelson via [email protected] or telephone +1 212. 645. 8006

New Yorkers, Take Back Your City

Jeremiah Moss is the pen name of the author of the blog Vanishing New York.

Jeremiah Moss is the pen name of the author of the blog Vanishing New York.

NEW YORK TIMES

The old-school gentrification of the 20th century, while harmful, wasn’t all bad. It made streets safer, created jobs and brought fresh vegetables to the corner store. Today, however, what we talk about when we talk about gentrification is actually a far more destructive process, one that I prefer to call hyper-gentrification.

Redirect tax breaks to mom-and-pops, pass an ordinance to control chain store sprawl, and strengthen residential rent regulation.

Unlike gentrification, in which the agents of change were middle-class settlers moving into working-class and poor neighborhoods, in hyper-gentrification the change comes from city government in collaboration with large corporations. Widespread transformation is intentional, massive and swift, resulting in a completely sanitized city filled with brand-name mega-developments built for the luxury class. The poor, working and middle classes are pushed out, along with artists, and the city goes stale. Urban scholar Neil Smith wrote extensively about the phenomenon, calling it “a systematic class-remaking of city neighborhoods.”

Cultivated by former mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, hyper-gentrification in New York was implemented via strategically planned mass rezonings, eminent domain and billions in tax breaks to corporations. This led to the eviction of countless residents and small businesses, destroying the fabric of our streets and putting the city’s soul on life support. To save it, we need politicians, activists and citizens to get tough and retake this city. Let’s drastically reduce tax breaks to corporations and redirect that money to mom-and-pops. Protect the city’s oldest small businesses by providing selective retail rent control, and implement the Small Business Survival Act to create fair rent negotiations. Pass a citywide ordinance to control the spread of chain stores. Strengthen residential rent regulation. Shop local and protest the corporate invasion of neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, too many New Yorkers say, “This is normal. The city always changes.” They’re in denial. This is not normal. It is state-sponsored, corporate-driven and turbo-charged.

The first step to healing is to admit we have a problem.

The old-school gentrification of the 20th century, while harmful, wasn’t all bad. It made streets safer, created jobs and brought fresh vegetables to the corner store. Today, however, what we talk about when we talk about gentrification is actually a far more destructive process, one that I prefer to call hyper-gentrification.

Redirect tax breaks to mom-and-pops, pass an ordinance to control chain store sprawl, and strengthen residential rent regulation.

Unlike gentrification, in which the agents of change were middle-class settlers moving into working-class and poor neighborhoods, in hyper-gentrification the change comes from city government in collaboration with large corporations. Widespread transformation is intentional, massive and swift, resulting in a completely sanitized city filled with brand-name mega-developments built for the luxury class. The poor, working and middle classes are pushed out, along with artists, and the city goes stale. Urban scholar Neil Smith wrote extensively about the phenomenon, calling it “a systematic class-remaking of city neighborhoods.”

Cultivated by former mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, hyper-gentrification in New York was implemented via strategically planned mass rezonings, eminent domain and billions in tax breaks to corporations. This led to the eviction of countless residents and small businesses, destroying the fabric of our streets and putting the city’s soul on life support. To save it, we need politicians, activists and citizens to get tough and retake this city. Let’s drastically reduce tax breaks to corporations and redirect that money to mom-and-pops. Protect the city’s oldest small businesses by providing selective retail rent control, and implement the Small Business Survival Act to create fair rent negotiations. Pass a citywide ordinance to control the spread of chain stores. Strengthen residential rent regulation. Shop local and protest the corporate invasion of neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, too many New Yorkers say, “This is normal. The city always changes.” They’re in denial. This is not normal. It is state-sponsored, corporate-driven and turbo-charged.

The first step to healing is to admit we have a problem.

#SAVENYC MEDIA

READ IT & WEEP

#SaveNYC

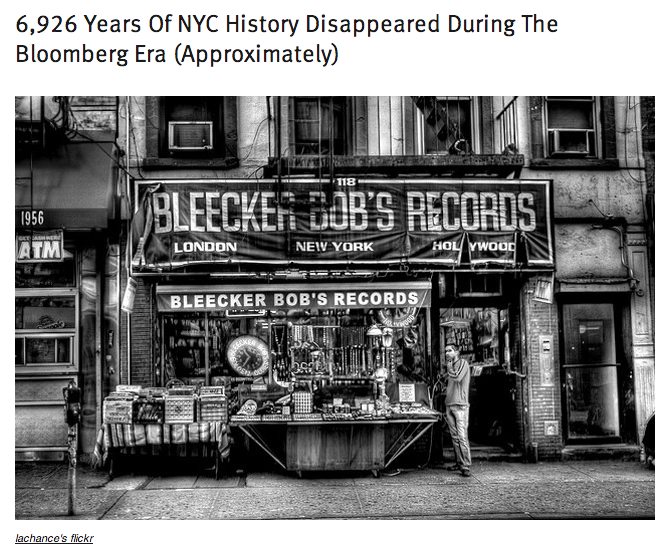

GOTHAMIST | By Ben Yakas in Arts & Entertainment on Jan 5, 2014

There's no denying that Mayor Bloomberg dramatically changed the landscape of NYC through bike lanes, new buildings construction, and rezoning. In some ways—like with improved and increased street space—this has been a very good thing. But in other ways—like the homelessness epidemic and with the loss of affordable housing to taxpayer subsidized high rises—it most certainly has not. And one of his worst legacies will be the incredible loss of beloved neighborhood businesses and restaurants over his 12 years in office.

Jeremiah Moss, the curator and chronicler of the changing face of NYC on Jeremiah's Vanishing New York, compiled an impressively depressing list of businesses that have disappeared since 2001—places that have been forced out because of rent hikes, that lost their leases when their building was sold, that were demolished for billion-dollar luxury condo projects.

It's a list where the phrase "a victim of soaring rents in a neighborhood populated as much by bankers as by bohemians" is all too accurate. Moss lists all the years these establishments were in business (ie, 150 years for Domino Sugar Factory, 45 years for Kenny's Castaway's), and came up with an astronomical figure: NYC lost at least 6,926 years of its history in 12 years.

In 2013 alone, we lost 836 years of history:

Stile's Market: 26 years Pushed out by landlord, to be demolished for luxury development5Pointz, formerly Phun Phactory: 20 years

White-washed by owner, to be demolished for luxury condo towers

Famous Roio’s/Ray’s Pizza: 40 years

Building sold

Ray Beauty Supply: 50 years

Property seized by landlord

Vercesi Hardware: 101 years

Building sold to be demolished for luxury condos

D’Auito’s Bakery: 89 years

Unknown

Odessa Restaurant: 48 years

Building sold, gastropub to move in, now for rent

Splash gay bar: 22 years

Lack of business

Paradise Café: 20 years

Rent hike

Big Nick’s Burger and Pizza Joint: 51 years

Rent increase from $42,000 to $60,000 a month

Max Fish: 24 years

Rent increase

Joe’s Dairy: 60 years

Cost of doing business

Bleecker Bob’s Records: 46 years

Rent hike

Blarney Cove: 50+ years

Evicted for new development

Sofia’s Italian restaurant: 35 years

Lost their lease

9th Street Bakery: 87 years

38% rent hike, replaced by juice-cleanse and smoothie shop

Capucine’s Italian restaurant: 33 years

Rent hike

Rawhide gay bar: 34 years

Rent hike, to be turned into a pizza chain from California

Some of these places of course would have disappeared anyway (as a commenter points out, "'Seized by landlord' and 'evicted' means non-payment of rent"), but most places seem to have been the victims of gentrification, rent increases, and the rising cost of surviving in NYC. We share Moss' hope that de Blasio will follow the lead of San Francisco in dealing with retail stores. In the meantime, let's appreciate the popovers while they're here.

There's no denying that Mayor Bloomberg dramatically changed the landscape of NYC through bike lanes, new buildings construction, and rezoning. In some ways—like with improved and increased street space—this has been a very good thing. But in other ways—like the homelessness epidemic and with the loss of affordable housing to taxpayer subsidized high rises—it most certainly has not. And one of his worst legacies will be the incredible loss of beloved neighborhood businesses and restaurants over his 12 years in office.

Jeremiah Moss, the curator and chronicler of the changing face of NYC on Jeremiah's Vanishing New York, compiled an impressively depressing list of businesses that have disappeared since 2001—places that have been forced out because of rent hikes, that lost their leases when their building was sold, that were demolished for billion-dollar luxury condo projects.

It's a list where the phrase "a victim of soaring rents in a neighborhood populated as much by bankers as by bohemians" is all too accurate. Moss lists all the years these establishments were in business (ie, 150 years for Domino Sugar Factory, 45 years for Kenny's Castaway's), and came up with an astronomical figure: NYC lost at least 6,926 years of its history in 12 years.

In 2013 alone, we lost 836 years of history:

Stile's Market: 26 years Pushed out by landlord, to be demolished for luxury development5Pointz, formerly Phun Phactory: 20 years

White-washed by owner, to be demolished for luxury condo towers

Famous Roio’s/Ray’s Pizza: 40 years

Building sold

Ray Beauty Supply: 50 years

Property seized by landlord

Vercesi Hardware: 101 years

Building sold to be demolished for luxury condos

D’Auito’s Bakery: 89 years

Unknown

Odessa Restaurant: 48 years

Building sold, gastropub to move in, now for rent

Splash gay bar: 22 years

Lack of business

Paradise Café: 20 years

Rent hike

Big Nick’s Burger and Pizza Joint: 51 years

Rent increase from $42,000 to $60,000 a month

Max Fish: 24 years

Rent increase

Joe’s Dairy: 60 years

Cost of doing business

Bleecker Bob’s Records: 46 years

Rent hike

Blarney Cove: 50+ years

Evicted for new development

Sofia’s Italian restaurant: 35 years

Lost their lease

9th Street Bakery: 87 years

38% rent hike, replaced by juice-cleanse and smoothie shop

Capucine’s Italian restaurant: 33 years

Rent hike

Rawhide gay bar: 34 years

Rent hike, to be turned into a pizza chain from California

Some of these places of course would have disappeared anyway (as a commenter points out, "'Seized by landlord' and 'evicted' means non-payment of rent"), but most places seem to have been the victims of gentrification, rent increases, and the rising cost of surviving in NYC. We share Moss' hope that de Blasio will follow the lead of San Francisco in dealing with retail stores. In the meantime, let's appreciate the popovers while they're here.

Starbucks Will Open in Original Bleecker Street Records Location #SAVENYC

A little bit punk and a little bit frappuccino | A recent real-estate industry notice indicates the lease on the 1,500-square-foot space was signed earlier this month, and the storefront at 239 Bleecker Street that was home to Bleecker Street Recordswill next become a Starbucks. The vinyl store thrived for more than two decades in its West Village home, but was forced to move to 188 West 4th Street after the landlord reportedly increased the rent to $27,000. (Nearby Bleecker Bob's, a favorite of Joey Ramone's, was not as lucky this time last year, when it closed forever to make way for an incoming frozen-yogurt store.) A spokesperson for the coffee chain, which now has more than 280 locations in the city, confirms 239 Bleecker will open this summer.

#SaveNYC

Pearl Paint Has Indeed Closed | #SAVENYC

That was fast: Just two weeks after the sales listing for its two buildings was discovered, Pearl Paint has closed. “The now-shuttered building, at 308 Canal, is up for sale, ending the store’s 50-year presence on the street and more than 80 years in the neighborhood,” says the Tribeca Trib. “(Pearl Paint opened on Church Street in 1933, selling house paint.)” We’ll have to see if the buildings (304-306 Canal) survive the change. According to the listing, “The building delivers over 2,000 SF of air rights. Due to the sizable floor plates, phenomenal location for retail (Canal) and residential (Lispenard), the building offers a great opportunity for a developer, investor and/or user. The space can be delivered vacant.”

SPIKE LEE: Open Letter on NYC | #SAVENYC

Director Spike Lee ("Do the Right Thing," "He Got Game," "Malcolm X") responds on WhoSay to A.O. Scott's New York Times article, "Whose Brooklyn Is It, Anyway?" (March 30, 2014). Scroll down for the original post.

A Letter To New York Times Film Critic Mr. A.O. Scott responding to his article in the Sunday Arts & Leisure Section, “WHOSE BROOKLYN IS IT, ANYWAY?”

Dear Mr. A.O. Scott, I have chose the platform of my Social Media to respond to you. I do not want the New York Times editing, rearranging my words, thoughts or even ignoring a letter to you. I’m writing what I feel and there is no need for somebody else at The New York Times to interpret it.

The Truth is The Truth. The Truth is The Light, and as they say in Brasil “One Finger Can’t Block The Sun.” The Truth is Gentrification is Great for the New Arrivals in Harlem, South Bronx, Bushwick, Red Hook, Bed-Stuy Do or Die and Fort Greene, and in many other cities across the U.S. But not so great for The Brown and Black Residents who have been in these Neighborhoods for decades and are being forced out, to the Suburbs, Down South or back to their Native Islands.

Your criticism of me as a hypocrite is lame, weak and not really thought out. You stated in your Article that because I live in The Upper East Side and I’m talking about Gentrification that makes me Hypocrite. The fact is where I live has nothing to do with it. Your argument is OKEY DOKE. If you did your research you would see I’m a product of The New York Public School System, from Kindergarten to graduating from John Dewey High School in Coney Island. I was born in Atlanta, Georgia and my Family moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn when I was Three. The Lees were the 1st Black Family to move into the predominantly Italian-American Brooklyn Neighborhood of Cobble Hill. My Parents bought their first home in 1968, a Brownstone in Fort Greene, where my Father still lives. Did you know his and a Next door Neighbor’s Brownstone were vandalized by Graffiti after my remarks on Gentrification at Pratt Institute? Curious you left that out of your article.

Mr. Scott, what you fail to understand is that I can live on The Moon and what I said is still TRUE. No matter where I choose to live that has nothing to do with it. I will always carry Brooklyn in my Blood, Heart and Soul. Did anyone call Jay-Z a Hypocrite when he helped with bringing The Nets from New Jersey to The Barclays Center in Brooklyn at the Corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenue? Hey Buddy, Jay-Z had been long, long gone from The Marcy Projects and Brooklyn a long, long, long time ago and more Power to my BK ALL DAY Brother. Should Jay-Z no longer mention Brooklyn in his Songs because he no longer resides there? You already know the answer to that one, Sir.

Let’s just say Mr. Scott, we follow your ill thought out, half developed argument that I’m a Hypocrite. Since you are a New York Times Film Critic this should be very easy for you. According to your logic I should not have Written and Directed JUNGLE FEVER because I have never lived in HARLEM and BENSONHURST. I should not have Directed CLOCKERS because I have never lived in Boerum Hill and the Gowanus Projects. I should have not Written and Directed HE GOT GAME because I have never lived in CONEY ISLAND. I should have never Directed my two Epic Documentaries on Hurricane Katrina – WHEN THE LEVEES BROKE and IF GOD IS WILLING AND DA CREEK DON’T RISE because I have never lived in NEW ORLEANS. Or maybe, perhaps I should have never WRITTEN and DIRECTED DO THE RIGHT THING because I have never, ever, ever lived in BED-STUY (DO OR DIE). Do you see where this is going?

In closing please understand it’s what you get growing up and learning on the Streets of Brooklyn that empowers you to go anywhere on this God’s Earth to “Do Ya Thang” to be successful in the path you have chosen. It doesn’t matter where you choose to live because Brooklyn goes where you go. It still lives inside Larry King, Sandy Koufax, Big Daddy Kane, Bernard and Albert King, Barry Manilow, Stephon Marbury, Rhea Perlman, Adam Sandler, Neil Sedaka, Jerry Seinfeld, Busta Rhymes, Mike Tyson, Harvey Keitel, Willie Randolph, Carmelo Anthony, Mel Brooks, Marisa Tomei, Marv Alvert, Darren Aronofsky, Pat Benatar, Larry David, Mos Def, Tony Danza, Alan Dershowitz, Neil Diamond, Richard Dreyfuss, Debbie Gibson, Rudy Giuliani, David Geffen, Lou Gossett, Jr., Elliott Gould, Mark Jackson, Jimmy Kimmel, Talib Kweli, Nia Long, Alyssa Milano, Stephanie Mills, Esai Morales, Chris Mullin, Chuck Schumer, Jimmy Smits, Joe Torre, Eli Wallach, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy, Woody Allen, Barbara Streisand and may I mention none of the above still reside in B.K., but they will always REPRESENT BROOKLYN. Mr. Scott, please learn “SPREADIN’ LOVE IS THE BROOKLYN WAY.”

WAKE UP

WE BEEN HERE

Spike Lee

Filmmaker

Fort Greene

Da Republic of Brooklyn, New York

YA-DIG? SHO-NUFF

And Dat’s Da Truth Ruth

A Letter To New York Times Film Critic Mr. A.O. Scott responding to his article in the Sunday Arts & Leisure Section, “WHOSE BROOKLYN IS IT, ANYWAY?”

Dear Mr. A.O. Scott, I have chose the platform of my Social Media to respond to you. I do not want the New York Times editing, rearranging my words, thoughts or even ignoring a letter to you. I’m writing what I feel and there is no need for somebody else at The New York Times to interpret it.

The Truth is The Truth. The Truth is The Light, and as they say in Brasil “One Finger Can’t Block The Sun.” The Truth is Gentrification is Great for the New Arrivals in Harlem, South Bronx, Bushwick, Red Hook, Bed-Stuy Do or Die and Fort Greene, and in many other cities across the U.S. But not so great for The Brown and Black Residents who have been in these Neighborhoods for decades and are being forced out, to the Suburbs, Down South or back to their Native Islands.

Your criticism of me as a hypocrite is lame, weak and not really thought out. You stated in your Article that because I live in The Upper East Side and I’m talking about Gentrification that makes me Hypocrite. The fact is where I live has nothing to do with it. Your argument is OKEY DOKE. If you did your research you would see I’m a product of The New York Public School System, from Kindergarten to graduating from John Dewey High School in Coney Island. I was born in Atlanta, Georgia and my Family moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn when I was Three. The Lees were the 1st Black Family to move into the predominantly Italian-American Brooklyn Neighborhood of Cobble Hill. My Parents bought their first home in 1968, a Brownstone in Fort Greene, where my Father still lives. Did you know his and a Next door Neighbor’s Brownstone were vandalized by Graffiti after my remarks on Gentrification at Pratt Institute? Curious you left that out of your article.

Mr. Scott, what you fail to understand is that I can live on The Moon and what I said is still TRUE. No matter where I choose to live that has nothing to do with it. I will always carry Brooklyn in my Blood, Heart and Soul. Did anyone call Jay-Z a Hypocrite when he helped with bringing The Nets from New Jersey to The Barclays Center in Brooklyn at the Corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenue? Hey Buddy, Jay-Z had been long, long gone from The Marcy Projects and Brooklyn a long, long, long time ago and more Power to my BK ALL DAY Brother. Should Jay-Z no longer mention Brooklyn in his Songs because he no longer resides there? You already know the answer to that one, Sir.

Let’s just say Mr. Scott, we follow your ill thought out, half developed argument that I’m a Hypocrite. Since you are a New York Times Film Critic this should be very easy for you. According to your logic I should not have Written and Directed JUNGLE FEVER because I have never lived in HARLEM and BENSONHURST. I should not have Directed CLOCKERS because I have never lived in Boerum Hill and the Gowanus Projects. I should have not Written and Directed HE GOT GAME because I have never lived in CONEY ISLAND. I should have never Directed my two Epic Documentaries on Hurricane Katrina – WHEN THE LEVEES BROKE and IF GOD IS WILLING AND DA CREEK DON’T RISE because I have never lived in NEW ORLEANS. Or maybe, perhaps I should have never WRITTEN and DIRECTED DO THE RIGHT THING because I have never, ever, ever lived in BED-STUY (DO OR DIE). Do you see where this is going?

In closing please understand it’s what you get growing up and learning on the Streets of Brooklyn that empowers you to go anywhere on this God’s Earth to “Do Ya Thang” to be successful in the path you have chosen. It doesn’t matter where you choose to live because Brooklyn goes where you go. It still lives inside Larry King, Sandy Koufax, Big Daddy Kane, Bernard and Albert King, Barry Manilow, Stephon Marbury, Rhea Perlman, Adam Sandler, Neil Sedaka, Jerry Seinfeld, Busta Rhymes, Mike Tyson, Harvey Keitel, Willie Randolph, Carmelo Anthony, Mel Brooks, Marisa Tomei, Marv Alvert, Darren Aronofsky, Pat Benatar, Larry David, Mos Def, Tony Danza, Alan Dershowitz, Neil Diamond, Richard Dreyfuss, Debbie Gibson, Rudy Giuliani, David Geffen, Lou Gossett, Jr., Elliott Gould, Mark Jackson, Jimmy Kimmel, Talib Kweli, Nia Long, Alyssa Milano, Stephanie Mills, Esai Morales, Chris Mullin, Chuck Schumer, Jimmy Smits, Joe Torre, Eli Wallach, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy, Woody Allen, Barbara Streisand and may I mention none of the above still reside in B.K., but they will always REPRESENT BROOKLYN. Mr. Scott, please learn “SPREADIN’ LOVE IS THE BROOKLYN WAY.”

WAKE UP

WE BEEN HERE

Spike Lee

Filmmaker

Fort Greene

Da Republic of Brooklyn, New York

YA-DIG? SHO-NUFF

And Dat’s Da Truth Ruth

Alec Baldwin: Good-bye, Public Life By Alec Baldwin | #SAVENYC

EDITED As told to Joe Hagan.

I’ve read where a number of people have felt that 2013 was a shitty year. For me, it was actually a great year, because my wife and I had a baby. But, yeah, everything else was pretty awful. And I find myself bitter, defensive, and more misanthropic than I care to admit. And I’m trying to understand what happened, how an altercation on the street, in which I was accused—wrongly—of using a gay slur, could have cascaded like this. There’s been a shift in my life. And it’s caused me to step back and say, This is happening for a reason.

I’ve had a relatively charmed life. I loved to be out in the city. New York was my town. I’ve had people come up to me and say, “You’re a great New Yorker. You’ve given your time and money to so many New York charities. You’re a great supporter of the arts. I like some of your movies—and some of your movies suck, actually.” (It’s New York, so people give you their unvarnished opinion.) But people in general had been very kind to me for years.

And then, last November, everything changed.

I haven’t changed, but public life has.

It used to be you’d go into a restaurant and the owner would say, “Do you mind if I take a picture of you and put it on my wall?” Sweet and simple. Now, everyone has a camera in their pocket. Add to that predatory photographers and predatory videographers who want to taunt you and catch you doing embarrassing things. (Some proof of which I have provided.) You’re out there in a world where if you do make a mistake, it echoes in a digital canyon forever.

And this isn’t the days of Rona Barrett and Ron Galella, who were viewed as outcasts or peripheral at best. Paparazzi today are part of a network that includes the Huffington Post and, much to my dismay, even NBC News, in their reliance on tabloid reporting.

Photographers today get right up in your face, my wife’s, my baby’s. They are baiting you. You can tell they want to get into it with you. Some bump into me or block the entrance to my apartment, frustrating my neighbors (some of whom may regret that I live in their building).

I’m self-aware enough to know that I am to blame for some of this. I definitely should not have reacted the way I did in some of these situations. I don’t have these issues with waiters, traffic cops, store clerks. I know there’s an impression that I’m someone who seeks to have violent confrontations with people. I don’t. Do I regret screaming at some guy who practically clipped my kid in the head with the lens of a camera? Yeah, I probably do, because it’s only caused me problems.

Broadway has changed, by my lights. The TV networks, too. New York has changed. Even the U.S., which is so preposterously judgmental now. The heart, the arteries of the country are now clogged with hate. The fuel of American political life is hatred. Who would ever dream that Obama would deserve to be treated the way he has been? The birth-certificate bullshit, which is just Obama’s version of Swiftboating. And all for the electoral nullification that seems like a cancer on the American system. But this is Roger Ailes. And Fox. And Breitbart. And this is all about hate. It’s Hate Incorporated. But the liberals have taken the bait and run in the same direction—and it’s just as corrosive. MSNBC, in its own way, is as full of shit, as redundant and as superfluous, as Fox.

I think America’s more fucked up now than it’s ever been. People are angry that in the game of musical chairs that is the U.S. economy, there are less seats at the table when the music stops. And at every recession, the music is stopping.

Am I bitter about some of the things that have happened to me in the past year? Yes, I’m a human being. I always had big ambitions. I had dreams of running for office at some point in the next five years. In the pyramid of decision-making in New York City politics, rich people come first, unions second, and rank-and-file New Yorkers come dead last. I wanted to change that. I wanted to find a way to lower the cost of the city government and thus reduce New York’s shameful tax burden. I would have decentralized the schools. My father was a public-school teacher. He always told me that although you could encourage a child to work hard, you could only go so far; that half the goal had to be achieved at home. As progressive as I’ve been in my politics, there are other things I don’t think of as liberal or progressive, just common sense. Of course, another thing I would have done—and this will not surprise anyone—is change the paparazzi law.

I’ve lived in New York since 1979. It was a place that they gave you your anonymity. And not just if you were famous. New Yorkers nodded at you. New Yorkers smiled at you at the Shakespeare & Co. bookshop. New Yorkers would make a terse comment to you. “Big fan,” they’d say. “Loved you in Streetcar,” they’d say. They signaled their appreciation of you very politely. To be a New Yorker meant you gave everybody five feet. You gave everybody their privacy. I recall how, in a big city, many people had to play out private moments in public: a woman sobbing at a pay phone (remember pay phones?), someone studying their paperwork, undisturbed, at the Oyster Bar, before catching the train. We allowed people privacy, we left them alone. And now we don’t leave each other alone. Now we live in a digital arena, like some Roman Colosseum, with our thumbs up or thumbs down.

My uncle was a lifelong New Yorker. He said, “New York is the place where if you really are one in a million, there’s seven other people just like you right here in town!” And I used to laugh at that. He’d say, “New York, millionaires and whores shoulder to shoulder on 57th Street. Some of them millionaires and whores!”

There was a time the entire world didn’t have a camera in their pocket—the first thing that cell phones did was to kill the autograph business. Nobody cares about your autograph. There are cameras everywhere, and there are media outlets for them to “file their story.” They take your picture in line for coffee. They’re trying to get a picture of your baby. Everyone’s got a camera. When they’re done, they tweet it. It’s … unnatural.

I did not have a happy family life a few years ago. I was divorced and I was very alienated from my daughter and I was out there cutting every ribbon and running around New York hosting events for different causes to supplant my loss, because I didn’t have a family to go home to. Now I don’t want to be Mr. Show Business anymore. I want the same thing everybody else wants. I want a happy home, and for the first time in my adult life, I have one. I love my wife more than anything in the world and I love my child more than anything else in the world and I don’t want that to change in any way.

I probably have to move out of New York. I just can’t live in New York anymore. Everything I hated about L.A. I’m beginning to crave. L.A. is a place where you live behind a gate, you get in a car, your interaction with the public is minimal. I used to hate that. But New York has changed. Manhattan is like Beverly Hills. And the soul of New York has moved to Brooklyn, where everything new and exciting seems to be. I have to accept that. I want my newest child to have as normal and decent a life as I can provide. New York doesn’t seem the place for that anymore.

It’s good-bye to public life in the way that you try to communicate with an audience playfully like we’re friends, beyond the work you are actually paid for. Letterman. Saturday Night Live. That kind of thing. I want to go make a movie and be very present for that and give it everything I have, and after we’re done, then the rest of the time is mine. I started out as an actor, where you seek to understand yourself using the words of great writers and collaborating with other creative people. Then I slid into show business, where you seek only an audience’s approval, whether you deserve it or not. I think I want to go back to being an actor now.

There’s a way I could have done things differently. I know that. If I offended anyone along the way, I do apologize. But the solution for me now is: I’ve lived this for 30 years, I’m done with it.

And, admittedly, this is how I feel in February of 2014.

Shia LaBeouf went to a film screening recently and he wore a bag over his head and the bag says I AM NOT FAMOUS ANYMORE. And there was truly a part of me that felt sorry for him, oddly enough.

This article appeared in the February 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

I’ve read where a number of people have felt that 2013 was a shitty year. For me, it was actually a great year, because my wife and I had a baby. But, yeah, everything else was pretty awful. And I find myself bitter, defensive, and more misanthropic than I care to admit. And I’m trying to understand what happened, how an altercation on the street, in which I was accused—wrongly—of using a gay slur, could have cascaded like this. There’s been a shift in my life. And it’s caused me to step back and say, This is happening for a reason.

I’ve had a relatively charmed life. I loved to be out in the city. New York was my town. I’ve had people come up to me and say, “You’re a great New Yorker. You’ve given your time and money to so many New York charities. You’re a great supporter of the arts. I like some of your movies—and some of your movies suck, actually.” (It’s New York, so people give you their unvarnished opinion.) But people in general had been very kind to me for years.

And then, last November, everything changed.

I haven’t changed, but public life has.

It used to be you’d go into a restaurant and the owner would say, “Do you mind if I take a picture of you and put it on my wall?” Sweet and simple. Now, everyone has a camera in their pocket. Add to that predatory photographers and predatory videographers who want to taunt you and catch you doing embarrassing things. (Some proof of which I have provided.) You’re out there in a world where if you do make a mistake, it echoes in a digital canyon forever.

And this isn’t the days of Rona Barrett and Ron Galella, who were viewed as outcasts or peripheral at best. Paparazzi today are part of a network that includes the Huffington Post and, much to my dismay, even NBC News, in their reliance on tabloid reporting.

Photographers today get right up in your face, my wife’s, my baby’s. They are baiting you. You can tell they want to get into it with you. Some bump into me or block the entrance to my apartment, frustrating my neighbors (some of whom may regret that I live in their building).

I’m self-aware enough to know that I am to blame for some of this. I definitely should not have reacted the way I did in some of these situations. I don’t have these issues with waiters, traffic cops, store clerks. I know there’s an impression that I’m someone who seeks to have violent confrontations with people. I don’t. Do I regret screaming at some guy who practically clipped my kid in the head with the lens of a camera? Yeah, I probably do, because it’s only caused me problems.

Broadway has changed, by my lights. The TV networks, too. New York has changed. Even the U.S., which is so preposterously judgmental now. The heart, the arteries of the country are now clogged with hate. The fuel of American political life is hatred. Who would ever dream that Obama would deserve to be treated the way he has been? The birth-certificate bullshit, which is just Obama’s version of Swiftboating. And all for the electoral nullification that seems like a cancer on the American system. But this is Roger Ailes. And Fox. And Breitbart. And this is all about hate. It’s Hate Incorporated. But the liberals have taken the bait and run in the same direction—and it’s just as corrosive. MSNBC, in its own way, is as full of shit, as redundant and as superfluous, as Fox.

I think America’s more fucked up now than it’s ever been. People are angry that in the game of musical chairs that is the U.S. economy, there are less seats at the table when the music stops. And at every recession, the music is stopping.

Am I bitter about some of the things that have happened to me in the past year? Yes, I’m a human being. I always had big ambitions. I had dreams of running for office at some point in the next five years. In the pyramid of decision-making in New York City politics, rich people come first, unions second, and rank-and-file New Yorkers come dead last. I wanted to change that. I wanted to find a way to lower the cost of the city government and thus reduce New York’s shameful tax burden. I would have decentralized the schools. My father was a public-school teacher. He always told me that although you could encourage a child to work hard, you could only go so far; that half the goal had to be achieved at home. As progressive as I’ve been in my politics, there are other things I don’t think of as liberal or progressive, just common sense. Of course, another thing I would have done—and this will not surprise anyone—is change the paparazzi law.

I’ve lived in New York since 1979. It was a place that they gave you your anonymity. And not just if you were famous. New Yorkers nodded at you. New Yorkers smiled at you at the Shakespeare & Co. bookshop. New Yorkers would make a terse comment to you. “Big fan,” they’d say. “Loved you in Streetcar,” they’d say. They signaled their appreciation of you very politely. To be a New Yorker meant you gave everybody five feet. You gave everybody their privacy. I recall how, in a big city, many people had to play out private moments in public: a woman sobbing at a pay phone (remember pay phones?), someone studying their paperwork, undisturbed, at the Oyster Bar, before catching the train. We allowed people privacy, we left them alone. And now we don’t leave each other alone. Now we live in a digital arena, like some Roman Colosseum, with our thumbs up or thumbs down.

My uncle was a lifelong New Yorker. He said, “New York is the place where if you really are one in a million, there’s seven other people just like you right here in town!” And I used to laugh at that. He’d say, “New York, millionaires and whores shoulder to shoulder on 57th Street. Some of them millionaires and whores!”

There was a time the entire world didn’t have a camera in their pocket—the first thing that cell phones did was to kill the autograph business. Nobody cares about your autograph. There are cameras everywhere, and there are media outlets for them to “file their story.” They take your picture in line for coffee. They’re trying to get a picture of your baby. Everyone’s got a camera. When they’re done, they tweet it. It’s … unnatural.

I did not have a happy family life a few years ago. I was divorced and I was very alienated from my daughter and I was out there cutting every ribbon and running around New York hosting events for different causes to supplant my loss, because I didn’t have a family to go home to. Now I don’t want to be Mr. Show Business anymore. I want the same thing everybody else wants. I want a happy home, and for the first time in my adult life, I have one. I love my wife more than anything in the world and I love my child more than anything else in the world and I don’t want that to change in any way.

I probably have to move out of New York. I just can’t live in New York anymore. Everything I hated about L.A. I’m beginning to crave. L.A. is a place where you live behind a gate, you get in a car, your interaction with the public is minimal. I used to hate that. But New York has changed. Manhattan is like Beverly Hills. And the soul of New York has moved to Brooklyn, where everything new and exciting seems to be. I have to accept that. I want my newest child to have as normal and decent a life as I can provide. New York doesn’t seem the place for that anymore.

It’s good-bye to public life in the way that you try to communicate with an audience playfully like we’re friends, beyond the work you are actually paid for. Letterman. Saturday Night Live. That kind of thing. I want to go make a movie and be very present for that and give it everything I have, and after we’re done, then the rest of the time is mine. I started out as an actor, where you seek to understand yourself using the words of great writers and collaborating with other creative people. Then I slid into show business, where you seek only an audience’s approval, whether you deserve it or not. I think I want to go back to being an actor now.

There’s a way I could have done things differently. I know that. If I offended anyone along the way, I do apologize. But the solution for me now is: I’ve lived this for 30 years, I’m done with it.

And, admittedly, this is how I feel in February of 2014.

Shia LaBeouf went to a film screening recently and he wore a bag over his head and the bag says I AM NOT FAMOUS ANYMORE. And there was truly a part of me that felt sorry for him, oddly enough.

This article appeared in the February 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.

#SAVENYC

Owner of Cafe La Bella Ferrara, Frank Angileri, in front of his closed cafe on Mulberry St., once a tourist mainstay of Little Italy.

BY JOE STEPANSKY , JASON SHEFTELL AND LARRY MCSHANE

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS PUBLISHED: SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2013, 10:22 PM

Raise the rents, take the cannoli: Little Italy is disappearing.

The downtown neighborhood — long a haven for immigrant families from the old country — was once threatened by an ever-expanding Chinatown. But now the fatal blow is being delivered by the gentrifiers.

Young professionals, expensive lofts and boutique shops are all moving in. Brooks Brothers, the epitome of conservative style, is considering a Little Italy outlet.

“The blocks used to be full of Italian families,” recalled local resident Sonny Mongielle, 85. “Every block represented a different region of Italy.

“But it’s just a matter of time before Little Italy is no more,” he said.

The most recent census delivered stunning news for the tract at the heart of Little Italy: The neighborhood is home to not a single Italian-born resident, down from 44 in the 2000 Census.

But the Chinese-born population of Little Italy is down, too — 31% — and the Asian immigrant population is also on the decline, falling 18.6% in the last decade.

What’s up are incomes and homogeneity.

The median pay of residents of Little Italy has risen 27% — and the population of residents earning more than $100,000 is soaring, up 156% over the last decade. The white population is up 33%.

Celebs such as director Sofia Coppola were among the well-to-do recently checking out condos at the Brewster Carriage House at Mott and Broome Sts. The properties sold for millions.

“The lofts are selling for higher and higher,” said Tim Bascom, owner of Bascom Real Estate. “It’s becoming a cool place to be. Young people love it, and can afford it.”

Faith Hope Consolo, retail chairman for Douglas Elliman, said Little Italy remains caught in a residential and retail shift.

“This is SoHo extended,” she said. “The little boutiques are in Nolita, but they are coming fast to Little Italy.”

There are still 44 distinct Italian restaurants, bakeries and cafes in Little Italy.

But tourist mainstays such as Ristorante S.P.Q.R. and Cafe La Bella Ferrara have closed. And even the new incarnation of Umberto’s Clam House, near the original Umberto’s where gangster “Crazy Joey” Gallo was killed in 1972, is facing a rent hike that will likely end its run.

At La Bella Ferrara, the monthly rent went from $7,000 to $17,000 in just two years — and the sad owners closed after 42 years in business.

“We serve dessert and coffee, we can’t afford that,” said co-owner Frank Angileri, 69. “They pushed us out. . . . Italian businesses can’t survive here, with the rising rents and the economy.

“It’s a shame, it’s such a shame. They kicked us out like dogs.”

At S.P.Q.R. on Mulberry St., the landlord, who upped the rent to $55,000, is already eying the space for condos.

Manager Mike Ahmed, a 32-year S.P.Q.R. veteran, recalled the glory days: Guests from around the world, people getting engaged or married at the 500-seat restaurant, important business meetings held over the linguine di mare.

“It’s become too hard to make a living out of this place,” he said with resignation. The soaring rents are “the start of a cancer we’re not going to be able to control,” he adds.

At Puglia Ristorante, the loss of customers forced the shutdown of two adjoining dining rooms in recent years.

The restaurant was temporarilty open just four days a week, but is now back on a seven-day-a-week schedule. Frank Medina, a real estate manager whose clientele includes the vintage eatery, says he’s reluctant to bring in another restaurant to the location.

“The only thing that’s keeping this area alive,” he said, “is the San Gennaro Festival and the Chinese counterfeit (products). It’s very bleak.

“The joke here is Little Italy is very little — and getting littler,” he added. “In 10 years, it’s hard to say what’ll happen to Little Italy.”

The disappearing businesses are changing the area’s familiar Italian look.

Julen Larrinaga, who works at the Grey Dog Cafe between Grand and Hester Sts., said out-of-towners are confused when they arrive at his place, where the gentrified offerings include scrambled eggs or granola for $9, a cheeseburger is $11 and “Michigan sandwiches” are $9.75.

“Tourists come into the shop and ask where Little Italy is,” said Larrinaga, 24. “I tell them they’re technically in it already.”

BY JOE STEPANSKY , JASON SHEFTELL AND LARRY MCSHANE

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS PUBLISHED: SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2013, 10:22 PM

Raise the rents, take the cannoli: Little Italy is disappearing.

The downtown neighborhood — long a haven for immigrant families from the old country — was once threatened by an ever-expanding Chinatown. But now the fatal blow is being delivered by the gentrifiers.

Young professionals, expensive lofts and boutique shops are all moving in. Brooks Brothers, the epitome of conservative style, is considering a Little Italy outlet.

“The blocks used to be full of Italian families,” recalled local resident Sonny Mongielle, 85. “Every block represented a different region of Italy.

“But it’s just a matter of time before Little Italy is no more,” he said.

The most recent census delivered stunning news for the tract at the heart of Little Italy: The neighborhood is home to not a single Italian-born resident, down from 44 in the 2000 Census.

But the Chinese-born population of Little Italy is down, too — 31% — and the Asian immigrant population is also on the decline, falling 18.6% in the last decade.

What’s up are incomes and homogeneity.

The median pay of residents of Little Italy has risen 27% — and the population of residents earning more than $100,000 is soaring, up 156% over the last decade. The white population is up 33%.

Celebs such as director Sofia Coppola were among the well-to-do recently checking out condos at the Brewster Carriage House at Mott and Broome Sts. The properties sold for millions.

“The lofts are selling for higher and higher,” said Tim Bascom, owner of Bascom Real Estate. “It’s becoming a cool place to be. Young people love it, and can afford it.”

Faith Hope Consolo, retail chairman for Douglas Elliman, said Little Italy remains caught in a residential and retail shift.

“This is SoHo extended,” she said. “The little boutiques are in Nolita, but they are coming fast to Little Italy.”

There are still 44 distinct Italian restaurants, bakeries and cafes in Little Italy.

But tourist mainstays such as Ristorante S.P.Q.R. and Cafe La Bella Ferrara have closed. And even the new incarnation of Umberto’s Clam House, near the original Umberto’s where gangster “Crazy Joey” Gallo was killed in 1972, is facing a rent hike that will likely end its run.

At La Bella Ferrara, the monthly rent went from $7,000 to $17,000 in just two years — and the sad owners closed after 42 years in business.

“We serve dessert and coffee, we can’t afford that,” said co-owner Frank Angileri, 69. “They pushed us out. . . . Italian businesses can’t survive here, with the rising rents and the economy.

“It’s a shame, it’s such a shame. They kicked us out like dogs.”

At S.P.Q.R. on Mulberry St., the landlord, who upped the rent to $55,000, is already eying the space for condos.

Manager Mike Ahmed, a 32-year S.P.Q.R. veteran, recalled the glory days: Guests from around the world, people getting engaged or married at the 500-seat restaurant, important business meetings held over the linguine di mare.

“It’s become too hard to make a living out of this place,” he said with resignation. The soaring rents are “the start of a cancer we’re not going to be able to control,” he adds.

At Puglia Ristorante, the loss of customers forced the shutdown of two adjoining dining rooms in recent years.

The restaurant was temporarilty open just four days a week, but is now back on a seven-day-a-week schedule. Frank Medina, a real estate manager whose clientele includes the vintage eatery, says he’s reluctant to bring in another restaurant to the location.

“The only thing that’s keeping this area alive,” he said, “is the San Gennaro Festival and the Chinese counterfeit (products). It’s very bleak.

“The joke here is Little Italy is very little — and getting littler,” he added. “In 10 years, it’s hard to say what’ll happen to Little Italy.”

The disappearing businesses are changing the area’s familiar Italian look.

Julen Larrinaga, who works at the Grey Dog Cafe between Grand and Hester Sts., said out-of-towners are confused when they arrive at his place, where the gentrified offerings include scrambled eggs or granola for $9, a cheeseburger is $11 and “Michigan sandwiches” are $9.75.

“Tourists come into the shop and ask where Little Italy is,” said Larrinaga, 24. “I tell them they’re technically in it already.”

#SAVENYC

EATER | BY GREG MORABITO 1/09/2014[Photo: The Gurgling Cod]

At last, Nicholas Gray, the proprietor of Gray's Papaya, speaks about the shuttering of his beloved Greenwich Village hot dog stand. The restaurateur tells Fork in the Road that the downtown outpost of his mini-chain did indeed fold because of a rent hike. Gray explains: "They wanted to raise my rent to $50,000 from $30,000...We're always looking for corners, but they're hard to find." So realtors, if you know of a corner space that's open downtown, with rent around 30K or less, you know who to talk to. As Sietsema and several commenters have noted, Gray's Papaya was perpetually busy until it closed.

· Gray's Papaya: One is the Loneliest Number [FitR]

·All Coverage of PapayaGate 2014 [~ENY~]

At last, Nicholas Gray, the proprietor of Gray's Papaya, speaks about the shuttering of his beloved Greenwich Village hot dog stand. The restaurateur tells Fork in the Road that the downtown outpost of his mini-chain did indeed fold because of a rent hike. Gray explains: "They wanted to raise my rent to $50,000 from $30,000...We're always looking for corners, but they're hard to find." So realtors, if you know of a corner space that's open downtown, with rent around 30K or less, you know who to talk to. As Sietsema and several commenters have noted, Gray's Papaya was perpetually busy until it closed.

· Gray's Papaya: One is the Loneliest Number [FitR]

·All Coverage of PapayaGate 2014 [~ENY~]

#SAVENYC

Late last week, 85-year-old West Village Spanish restaurant El Faro wasshuttered by the DOH after racking up 57 violation points. Now, DNAinfo learns that the restaurant will stay closed until the owner, Mark Lurgis, can raise money to pay off the DOH fines and debts owed to purveyors, plus funds to finance a renovation of the space to bring it up to code. He estimates that the he needs $80,000 to reopen the restaurant.

Lurgis remarks, "We're exploring our options now, but we're limited financially." Apparently, the restaurant has received calls and emails of support from customers around the world since it closed last week. Lurgis explains that El Faro still has a devoted clientele, noting, "People have their packages delivered to us. It's like an extension of their house...We delivered food to some of our elderly [customers] and even brought them milk and bread if they couldn't leave home." Hopefully, Lurgis and his family will find a way to raise the money and reopen before the space is snatched up and turned into a fro-yo shop or a bro-bar.

Lurgis remarks, "We're exploring our options now, but we're limited financially." Apparently, the restaurant has received calls and emails of support from customers around the world since it closed last week. Lurgis explains that El Faro still has a devoted clientele, noting, "People have their packages delivered to us. It's like an extension of their house...We delivered food to some of our elderly [customers] and even brought them milk and bread if they couldn't leave home." Hopefully, Lurgis and his family will find a way to raise the money and reopen before the space is snatched up and turned into a fro-yo shop or a bro-bar.

#SAVENYC

WALL ST JOURNAL | MARA GAY | 29 MARCH 2013

When the Rawhide bar opened in Chelsea in 1979, it was, for some, an intimidating presence. Dark and foreboding, it attracted a gay clientele with a fondness for leather and motorcycles.

As Chelsea changed, the Rawhide has stayed the same. Its customers grew more mainstream and its neighbors more accepting.

But the bar held on to a gritty vibe that stubbornly recalled a different era, even as luxury high-rises sprung up around it and more families pushed strollers past its doors. The most distinctive feature of the Rawhide's black awning: the "e" in its name stretched into a string of barbed wire.

On Saturday, the bar, which sits at the corner of Eighth Avenue and West 21st Street, will close its doors. It plans to mark the moment with one final party.

"It's the end of Chelsea as we know it," longtime patron Andrew Loren Resto said in the dimly-lit, wood-paneled space this week, the bar's signature motorcycle hanging from the ceiling behind him. "It was just the last little bit of edge out here. And now it's going to be gone."

Owner Jason Gudgeon said he couldn't come to an agreement with the landlord, who declined to comment. He said he plans to reopen the bar elsewhere in Manhattan later this year.

"Chelsea isn't the gay scene it once was," Mr. Gudgeon said. "This bar was always a throwback to the gay bars of the 1970s, where it was dark, it was dangerous. When you set foot in it, you were an outlaw. Now the Rawhide is an outlier in the neighborhood. It doesn't fit in anymore."

The Rawhide helped usher in Chelsea's arrival as one of the city's most vibrant gay enclaves. Jon Knowles, 69 years old, said he first started going to the bar in the early days of the AIDS crisis. "All day we were working with people who were dying and desperate," he said. "This bar was very affirming. It was the one place in New York where it didn't feel like the world was coming to an end."

Many of Chelsea's shops display rainbow stickers, and stores including bakeries and lingerie shops market themselves to a gay clientele. But many say the soul of the city's gay scene, years ago centered in the West Village, has moved further northward again, this time to Hell's Kitchen.

"It's a trend, for sure," said Sam DeFranceschi, a real-estate broker who has worked in Chelsea for years. "I'm getting customers who used to be attached to Chelsea and are starting to consider living farther uptown, which in turn is making that area more interesting," he said.

Stephen Hoban, an editor who lives around the corner from the Rawhide with his wife and young son, said he was disappointed to hear about its closing. "Oh no! That's too bad!" he said, pushing his son down West 21st Street. "It's getting boring," the 36-year-old said. "I mean, they just opened a 7-11 down the block."

Some gay men interviewed in Chelsea said the Rawhide's heyday had come and gone. "It was edgy once, but it's outlived its time," said Arthur Brantley, 46, who has lived in Chelsea for more than two decades.

But even those who don't frequent the bar said it helped bolster the unique character of a neighborhood that has grown more affluent and mainstream, and has come to include high-end residential development and upscale amenities such as the High Line and Chelsea Market.

"It was an institution," said Michael Flaherty, an architect who lives in Chelsea. "Now it'll be another nail salon or yogurt place," he said. "We're supposed to be New York, and now we're becoming just like any other place in America."

In the eyes of some, though, the changes in the city's gay scene are, in a way, a sign of progress.

"We have assimilated. We do not need the safety of numbers anymore," Mr. Resto said. "We have babies. We have mortgages. We marched in the street for all this s— and we got it. And this is it."

Michael O'Neill, a longtime bartender at the Rawhide, agreed: "We used to stay in our own little neighborhoods, just like ethnic enclaves, but it's more spread out now, because we're more accepted."

When the Rawhide bar opened in Chelsea in 1979, it was, for some, an intimidating presence. Dark and foreboding, it attracted a gay clientele with a fondness for leather and motorcycles.

As Chelsea changed, the Rawhide has stayed the same. Its customers grew more mainstream and its neighbors more accepting.

But the bar held on to a gritty vibe that stubbornly recalled a different era, even as luxury high-rises sprung up around it and more families pushed strollers past its doors. The most distinctive feature of the Rawhide's black awning: the "e" in its name stretched into a string of barbed wire.

On Saturday, the bar, which sits at the corner of Eighth Avenue and West 21st Street, will close its doors. It plans to mark the moment with one final party.

"It's the end of Chelsea as we know it," longtime patron Andrew Loren Resto said in the dimly-lit, wood-paneled space this week, the bar's signature motorcycle hanging from the ceiling behind him. "It was just the last little bit of edge out here. And now it's going to be gone."

Owner Jason Gudgeon said he couldn't come to an agreement with the landlord, who declined to comment. He said he plans to reopen the bar elsewhere in Manhattan later this year.

"Chelsea isn't the gay scene it once was," Mr. Gudgeon said. "This bar was always a throwback to the gay bars of the 1970s, where it was dark, it was dangerous. When you set foot in it, you were an outlaw. Now the Rawhide is an outlier in the neighborhood. It doesn't fit in anymore."

The Rawhide helped usher in Chelsea's arrival as one of the city's most vibrant gay enclaves. Jon Knowles, 69 years old, said he first started going to the bar in the early days of the AIDS crisis. "All day we were working with people who were dying and desperate," he said. "This bar was very affirming. It was the one place in New York where it didn't feel like the world was coming to an end."

Many of Chelsea's shops display rainbow stickers, and stores including bakeries and lingerie shops market themselves to a gay clientele. But many say the soul of the city's gay scene, years ago centered in the West Village, has moved further northward again, this time to Hell's Kitchen.

"It's a trend, for sure," said Sam DeFranceschi, a real-estate broker who has worked in Chelsea for years. "I'm getting customers who used to be attached to Chelsea and are starting to consider living farther uptown, which in turn is making that area more interesting," he said.

Stephen Hoban, an editor who lives around the corner from the Rawhide with his wife and young son, said he was disappointed to hear about its closing. "Oh no! That's too bad!" he said, pushing his son down West 21st Street. "It's getting boring," the 36-year-old said. "I mean, they just opened a 7-11 down the block."

Some gay men interviewed in Chelsea said the Rawhide's heyday had come and gone. "It was edgy once, but it's outlived its time," said Arthur Brantley, 46, who has lived in Chelsea for more than two decades.

But even those who don't frequent the bar said it helped bolster the unique character of a neighborhood that has grown more affluent and mainstream, and has come to include high-end residential development and upscale amenities such as the High Line and Chelsea Market.

"It was an institution," said Michael Flaherty, an architect who lives in Chelsea. "Now it'll be another nail salon or yogurt place," he said. "We're supposed to be New York, and now we're becoming just like any other place in America."

In the eyes of some, though, the changes in the city's gay scene are, in a way, a sign of progress.

"We have assimilated. We do not need the safety of numbers anymore," Mr. Resto said. "We have babies. We have mortgages. We marched in the street for all this s— and we got it. And this is it."

Michael O'Neill, a longtime bartender at the Rawhide, agreed: "We used to stay in our own little neighborhoods, just like ethnic enclaves, but it's more spread out now, because we're more accepted."

#SAVENYC

GRUB STREET 7/31/13 By Lissa Townsend Rodgers

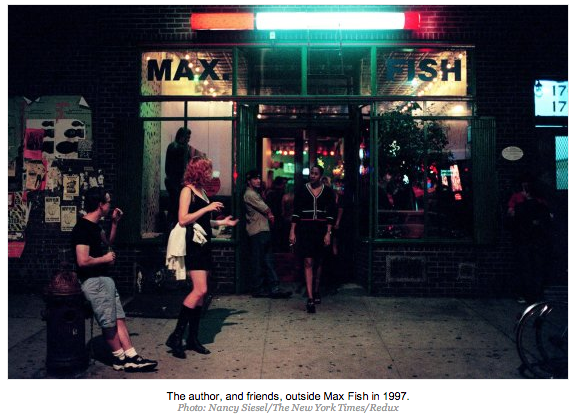

I don’t remember the first time I went to Max Fish, but I remember the first time I didn’t. I was showing downtown Manhattan, circa 1990, to a friend from high school. It was on Ludlow Street, past the pink light and protein smell of Katz’s into a dark block of shuttered storefronts and shadowy figures. When we got to the big windows of the bar, I hesitated. The music was unfamiliar; the crowd looked older and wised-up. My savoir faire failed, I mumbled some kind of excuse and we retreated to more familiar, low-key environs. Five years later, I was hanging out at Max Fish regularly enough that I sent postcards and brought gifts (of Everclear) from vacations. I went there still stained and sweaty from painting my friends’ apartment, I went after dinner at Sparks andTosca at the Met. Now the bar that inaugurated and endured the changes to its Lower East Side neighborhood is finally closed. It may not be the end of the bar — it’s moving to Brooklyn — but it is the end of an era.

The lighting was probably my excuse the first time. Max Fish had to be the brightest bar … ever. It was lighting better suited to an interrogation or an autopsy, illuminating artwork ranging from artists whose work now resides in museum collections to those whose only other showing was on a refrigerator. The permanent collection hung over the bar — the bas-relief pompadoured mook, the mutilated Julio Iglesias ad, a three-foot nail sticking out of the wall. Taylor Mead, the poet and Warhol star, always sat under the nail. We’d talk about MGM and RKO — he liked me because I “looked like [his] favorite star, Alice Faye” and because I knew who Alice Faye was. As one patron pointed out, Max Fish offered “a bridge between the old East Village/LES of the junkies and Warhol types and the art-directed new one.” Old bohemians who’d been around since the Velvet Underground lived across the street clinked glasses with the few-years-outta-the-suburbs kids who were still figuring out who they'd be: "I used to order Cosmos there," one patron groaned to me. "How confused was I? I hadn't seen Sex and the City. I couldn't afford cable."

The bartenders were equally adroit at being charming or dismissive and had an unerring instinct for who deserved which treatment. Allan looked like Billy Strayhorn, could face down a loaded gun without blinking, and was rumored to be anywhere from 25 to 52. Harry was one of those New York City lifers who knows everybody, from the guy who headlined the Garden last night to your friend he went to Stuyvesant with. There was the sweet country boy, the cute skateboarder, the girl with the painted eyebrows, the perpetually bemused Euro chick, a couple of guitarists, a few folks with permanent paint under their fingernails. The front booth facing the window was the best see-and-be-seen spot: Stuff in nine friends, yak about Céline or the Supremes, paint the nails of Cooper Union boys, and appraise people as they came in.

Max Fish was the unofficial clubhouse of New York indie rock (and I think it was the official clubhouse of Matador Records). If you wanted to join a band, sign a band, or hang out with a band, this was the place. There was the night a musician friend and I flirted with each other and whatever record label guy was buying drinks for the booth. (I don’t remember whether he was Interscope, Warner, or Dreamworks, but he brought his own cocktail parasols.)

Naturally, any bar so overrun by musicians would have a kickass jukebox. Being selected for the rotation at Max Fish meant a band had officially arrived. You played your friends’ CDs when sober and your crushes’ when drunk. Not that it was all hip. One late night, several of us began frantically doing the twist to Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy” as one of the musicians on said jukebox climbed atop a chair, doffed her aviator shades, and began yelling, “Fuck being cool! Fuck the East Village!” Nostalgia and irony are everywhere now, but back then it was a sort of spontaneously goofy reminder of the geeks most of us once were.

Then there was the bathroom — technically two bathrooms, but somebody had flooded the other one. Or they were getting high in it. Or having sex. Inside, it was like the hot box from Cool Hand Luke, but adorned by a cave painting collaboration between Timothy Leary, Keith Haring, and a 9-year-old boy with Tourette's. The aroma was supplied by Lysol and the Mexican restaurant down the block — not a romantic setting, but somehow conducive to making out with someone else’s boyfriend while his girlfriend pounded on the door. “Max Fish is responsible for my only ever one-night stand,” one regular told me. “I found out later he was on The Adventures of Pete and Pete. Talk about dating myself.”

Max Fish became a mandatory stop on any night out on the Lower East Side, which seemed to have more stops all of the time. The adjacent Pink Pony Café had sandwiches and another bathroom; both were welcome sights around 1 a.m. The Alleged Gallery offered the more serious artists a (somewhat) less boozy place to show their work. Arlene's Grocery and Mercury Lounge gave the musicians gigs. A bar opened up across the street to catch the runoff. Then another. Another. Then came the New York Times writeup in 1997: “The New Bohemia: East of Soho, But Still Unspoiled.” The title rendered itself obsolete upon publishing: Once it’s a full-color half-page, it’s spoiled.

And what was that half-page color photo of? Max Fish. With me and two of my friends standing in front. We had stopped by, someone who we thought was an NYU student was snapping photos, so we just ignored her. The weekend after the photo ran, Allan told us they were slammed and we stayed away, a little guilty.

Many of the newbies didn’t leave. And more came. The bits and pieces from which we had assembled our little boho personas suddenly went mass. We had stumbled across things on late-night TV, dug for them in crates, or idly picked some bit of ephemera up off of a “25 cents only” shelf. Newbies Googled it. And you can only search for what’s already there. Years ago, I had one friend with a mustache, tats, and trucker hat who was into bacon and bourbon — one. Suddenly, there were 25, 50, 100 clones of him. One day scientists may well be able to pinpoint the birth of the hipster to somewhere between the pool table and the back booth at Max Fish.

Last time I was back in the neighborhood — Citibikes now stand where dope dealers used to shuffle and mutter — there was a small crowd outside Max Fish, Allan checking I.D.s. We caught up, talked a little about the friends who had drifted off. We didn't talk about how things have changed — a look down the block and a shared roll of the eyes was enough. Brooklyn didn't seem like such a bad idea after all.

I don’t remember the first time I went to Max Fish, but I remember the first time I didn’t. I was showing downtown Manhattan, circa 1990, to a friend from high school. It was on Ludlow Street, past the pink light and protein smell of Katz’s into a dark block of shuttered storefronts and shadowy figures. When we got to the big windows of the bar, I hesitated. The music was unfamiliar; the crowd looked older and wised-up. My savoir faire failed, I mumbled some kind of excuse and we retreated to more familiar, low-key environs. Five years later, I was hanging out at Max Fish regularly enough that I sent postcards and brought gifts (of Everclear) from vacations. I went there still stained and sweaty from painting my friends’ apartment, I went after dinner at Sparks andTosca at the Met. Now the bar that inaugurated and endured the changes to its Lower East Side neighborhood is finally closed. It may not be the end of the bar — it’s moving to Brooklyn — but it is the end of an era.

The lighting was probably my excuse the first time. Max Fish had to be the brightest bar … ever. It was lighting better suited to an interrogation or an autopsy, illuminating artwork ranging from artists whose work now resides in museum collections to those whose only other showing was on a refrigerator. The permanent collection hung over the bar — the bas-relief pompadoured mook, the mutilated Julio Iglesias ad, a three-foot nail sticking out of the wall. Taylor Mead, the poet and Warhol star, always sat under the nail. We’d talk about MGM and RKO — he liked me because I “looked like [his] favorite star, Alice Faye” and because I knew who Alice Faye was. As one patron pointed out, Max Fish offered “a bridge between the old East Village/LES of the junkies and Warhol types and the art-directed new one.” Old bohemians who’d been around since the Velvet Underground lived across the street clinked glasses with the few-years-outta-the-suburbs kids who were still figuring out who they'd be: "I used to order Cosmos there," one patron groaned to me. "How confused was I? I hadn't seen Sex and the City. I couldn't afford cable."

The bartenders were equally adroit at being charming or dismissive and had an unerring instinct for who deserved which treatment. Allan looked like Billy Strayhorn, could face down a loaded gun without blinking, and was rumored to be anywhere from 25 to 52. Harry was one of those New York City lifers who knows everybody, from the guy who headlined the Garden last night to your friend he went to Stuyvesant with. There was the sweet country boy, the cute skateboarder, the girl with the painted eyebrows, the perpetually bemused Euro chick, a couple of guitarists, a few folks with permanent paint under their fingernails. The front booth facing the window was the best see-and-be-seen spot: Stuff in nine friends, yak about Céline or the Supremes, paint the nails of Cooper Union boys, and appraise people as they came in.

Max Fish was the unofficial clubhouse of New York indie rock (and I think it was the official clubhouse of Matador Records). If you wanted to join a band, sign a band, or hang out with a band, this was the place. There was the night a musician friend and I flirted with each other and whatever record label guy was buying drinks for the booth. (I don’t remember whether he was Interscope, Warner, or Dreamworks, but he brought his own cocktail parasols.)

Naturally, any bar so overrun by musicians would have a kickass jukebox. Being selected for the rotation at Max Fish meant a band had officially arrived. You played your friends’ CDs when sober and your crushes’ when drunk. Not that it was all hip. One late night, several of us began frantically doing the twist to Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy” as one of the musicians on said jukebox climbed atop a chair, doffed her aviator shades, and began yelling, “Fuck being cool! Fuck the East Village!” Nostalgia and irony are everywhere now, but back then it was a sort of spontaneously goofy reminder of the geeks most of us once were.

Then there was the bathroom — technically two bathrooms, but somebody had flooded the other one. Or they were getting high in it. Or having sex. Inside, it was like the hot box from Cool Hand Luke, but adorned by a cave painting collaboration between Timothy Leary, Keith Haring, and a 9-year-old boy with Tourette's. The aroma was supplied by Lysol and the Mexican restaurant down the block — not a romantic setting, but somehow conducive to making out with someone else’s boyfriend while his girlfriend pounded on the door. “Max Fish is responsible for my only ever one-night stand,” one regular told me. “I found out later he was on The Adventures of Pete and Pete. Talk about dating myself.”

Max Fish became a mandatory stop on any night out on the Lower East Side, which seemed to have more stops all of the time. The adjacent Pink Pony Café had sandwiches and another bathroom; both were welcome sights around 1 a.m. The Alleged Gallery offered the more serious artists a (somewhat) less boozy place to show their work. Arlene's Grocery and Mercury Lounge gave the musicians gigs. A bar opened up across the street to catch the runoff. Then another. Another. Then came the New York Times writeup in 1997: “The New Bohemia: East of Soho, But Still Unspoiled.” The title rendered itself obsolete upon publishing: Once it’s a full-color half-page, it’s spoiled.

And what was that half-page color photo of? Max Fish. With me and two of my friends standing in front. We had stopped by, someone who we thought was an NYU student was snapping photos, so we just ignored her. The weekend after the photo ran, Allan told us they were slammed and we stayed away, a little guilty.

Many of the newbies didn’t leave. And more came. The bits and pieces from which we had assembled our little boho personas suddenly went mass. We had stumbled across things on late-night TV, dug for them in crates, or idly picked some bit of ephemera up off of a “25 cents only” shelf. Newbies Googled it. And you can only search for what’s already there. Years ago, I had one friend with a mustache, tats, and trucker hat who was into bacon and bourbon — one. Suddenly, there were 25, 50, 100 clones of him. One day scientists may well be able to pinpoint the birth of the hipster to somewhere between the pool table and the back booth at Max Fish.

Last time I was back in the neighborhood — Citibikes now stand where dope dealers used to shuffle and mutter — there was a small crowd outside Max Fish, Allan checking I.D.s. We caught up, talked a little about the friends who had drifted off. We didn't talk about how things have changed — a look down the block and a shared roll of the eyes was enough. Brooklyn didn't seem like such a bad idea after all.

#SAVENYC

GOTHAMIST | By Jen Carlson in Food on Aug 27, 2013

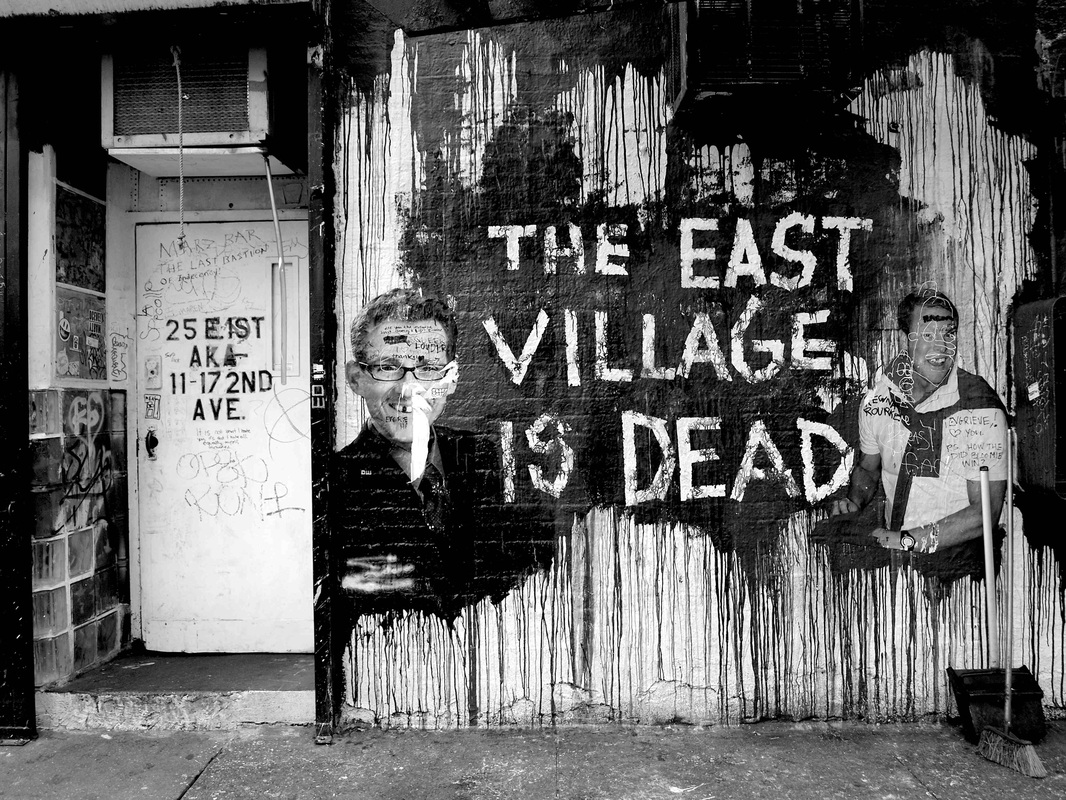

Odessa, the East Village bar next to the restaurant of the same name, is closing after 33 years. Forever. The end. Last call. Closing time. Say goodbye to your youth. The East Village is dead. RIP old New York. The rent is too damn high. ETC. To be clear, and as illustrated in the above image, the restaurant—where you soak up the night's alcohol with grilled cheese and fried eggplant—will remain open. But Odessa's bar next door, where you procure that alcohol that led you to the grilled cheese, is closing. And it's all happening this weekend. EV Grieve spotted their goodbye letter this week.

Odessa, the East Village bar next to the restaurant of the same name, is closing after 33 years. Forever. The end. Last call. Closing time. Say goodbye to your youth. The East Village is dead. RIP old New York. The rent is too damn high. ETC. To be clear, and as illustrated in the above image, the restaurant—where you soak up the night's alcohol with grilled cheese and fried eggplant—will remain open. But Odessa's bar next door, where you procure that alcohol that led you to the grilled cheese, is closing. And it's all happening this weekend. EV Grieve spotted their goodbye letter this week.

#SAVENYC

NEW YORK OBSERVER | BY KIM VELSEY | 8/22/13

It is, at this point, a story so common, the difference in details so slight, that even the most heartfelt of tributes can take on the tone of cliche—yet another beloved independent business shouldered out by a rent increase, yet another loss for a neighborhood in danger of losing its soul.

But at least this once, the ending is bittersweet rather than tragic. Bleecker Street Records, where music lovers, vinyl aficionados and NYU kids on the hunt for posters to lend their dorm rooms an air of authenticity have congregated for the last 20 years, is losing its home to a rent increase. The good news is that it’s relocating to a space nearby, on West 4th, between Sixth and Seventh, reports Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York. The move is more than a little unfortunate given the business’s name, but it’s a far better fate than the one that befell Bleecker Bob’s Records, which lost its lease to a frozen yogurt joint this spring and despite some talk of re-opening elsewhere, has yet to do so.

Bleecker Street Records was reportedly ousted from their space at 239 Bleecker by a rent increase that would have required the store pay $27,000 a month in rent. Fortunately, the store has found a new place in the neighborhood—no small feat given the escalating rents and the competition from stores intent on replicating the vibe of an outdoor shopping mall or a high-end highway rest stop: the advertisement for Bleecker Street Records’ former space boasted of its proximity to Amy’s Bread, David’s Tea, L’Occitane and 16 Handles.

True, the heyday of record stores has come and gone, probably never to return, but if there is any place with enough of a music loving community to support one, it would be Manhattan. Fortunately, Bleecker Street has managed to land on its feet—for now. As a Bleecker Bob’s employee was quoted as saying in a Spin article on the store’s last days: “This is a landlord’s town now.”

It is, at this point, a story so common, the difference in details so slight, that even the most heartfelt of tributes can take on the tone of cliche—yet another beloved independent business shouldered out by a rent increase, yet another loss for a neighborhood in danger of losing its soul.